If Denmark Vesey had succeeded in his plan, the well-respected minister, carpenter and activist would have masterminded the biggest slave revolt in history.

The freedom fighter was born a slave in 1767. His original name was Telemanque. At age 14, the boy, by now called Denmark, was sold to a slave trader known as Captain John Vesey as part of a 390-person bounty that Vesey brought from St. Thomas, a major slave port in the Caribbean, to Haiti. He was put to work on a sugar cane plantation.

Young Denmark did not like hard labor and didn’t last for long. One day, he angered his new master by dropping to the ground in an epileptic seizure, knowing that it would make him unfit for field work. The next time Vesey came to call, the owner gave Denmark back to him, deeming him “unfit goods.”

Denmark stayed with Vesey and never feigned another seizure. For the next two years, he sailed with the captain as he carried out his heinous duties of collecting slaves from Africa and delivering them to the West Indies.

In 1783, the captain decided to give up slave trading and settled in Charleston, S.C. Denmark remained as his personal servant for the next 17 years, taking his last name as was the custom for slaves.

In 1800, he won a $1,500 lottery. The first thing he purchased was his freedom, for $600. He was not, however, able to buy the freedom of his wife and two children. This angered him and set him on a mission to free his people from slavery.

He used his remaining winnings to set up a carpentry business, which thrived. Despite the fact that he was a free man, financially well-off with a successful business, Vesey never stopped thinking about breaking his people free from the shackles of slavery. He was determined to make it happen.

In 1816, Vesey and other free Blacks formed the African Methodist Church in Charleston, where he served as minister. The congregation began pooling money together to buy the freedom of slaves. Vesey likened the plight of the captive African slaves to that of the captive Israelites of the Old Testament. At nearly every meeting, he read from the Bible about how the children of Israel were delivered from bondage in Egypt and preached that Black people would be, too. By 1820, the congregation of the African Church had swelled to 3,000 members.

Whites carefully watched the activities, routinely disrupting services and arresting members. In 1820, the church was closed.

The Conspiracy

Vesey and the other church leaders, tired and angry about the relentless persecution and wanting to be free of white rule, began planning an insurrection. Vesey traveled around, spreading his message and gaining recruits. By 1822, he had some 9,000 participants.

Vesey knew the horrors of slavery first hand. Since he had lived in St. Dominique as a youth, he followed the events there with particular interest. He was thrilled at the success of the slave rising of 1791, where Blacks had chased out the slave owners and taken control of the colony. In 1804, St. Dominique became the nation of Haiti. If rebellion could work there, why not in Charleston?

Inspired by the events in Haiti, Vesey came up with an elaborate plan of his own. Charleston’s slaves would free themselves from bondage and seize the city. Men from the area and surrounding plantations would attack the city, take control of the guardhouse and block the bridges and roads, killing every white person in sight. An African priest from Mozanbique named Gullah Jack Pritchard helped Vesey gain support. The plan was two years in the making and was carefully detailed.

The uprising date was set for Sunday, July 14, 1822, at midnight. But it was not to be.

Betrayal, Trial and Execution

A plan this big and elaborate was impossible to keep secret. Too many people knew the major details and who the leaders were. Knowing that many house slaves were loyal to their masters, Vesey made sure they were not included. But despite his best efforts, the plan was exposed.

On May 30, 1822, a slave named George Wilson told his master about the planned insurrection. As a reward, he was given his freedom. Charleston authorities moved in fast on Vesey and his followers.

Realizing the betrayal, Vesey burned the lists of names of those involved. He and his top leaders, including Pritchard, were rounded up after a two-day search.

The details of the so-called “Vesey Conspiracy” were revealed during the trial. Whites were horrified to learn that the plan included killing every white person on the spot, as had been done in St. Dominique. Between 6,000 and 9,000 people were implicated. Eventually, the group had planned to use Charleston’s ships to escape to Haiti.

Vesey was condemned to death, along with Pritchard and 34 others. Forty-three more were sent to plantations in the West Indies.

On July 2, 1822, Vesey and five others were executed by hanging. Federal troops were called in because of large pro-Vesey demonstrations. Pritchard was executed days later.

While Vesey’s plan inspired admiration, it ultimately made life more difficult for South Carolina’s Blacks. Whites panicked at what might have happened. Movement for slaves was even more restricted, and freed slaves could no longer enter the ports. A military garrison was put into place to make sure that slaves never had an opportunity to revolt again.

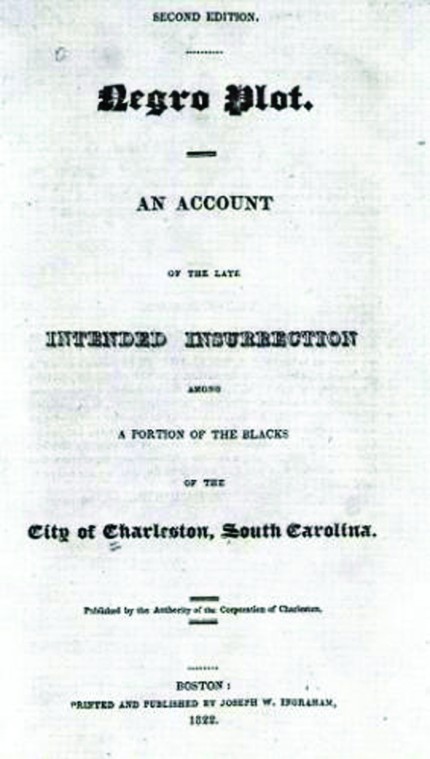

In August of 1822, a report titled “Negro Plot,” describing the insurrection in detail, was published. It sold for 25 cents a copy.

The report was the account of the plan given by J. Hamilton, who was the city’s intended mayor. Hamilton prefaced his account by noting:

“I have not been insensible as to what it might be politic either to publish or suppress. I have deemed a full publication as the most judicious course…There can be no harm in the salutary inculcation of one lesson, among a certain portion of our population, that there is nothing they are bad enough to do, that we are not powerful enough to punish.”

After Vesey was executed, the African Church was destroyed. Though distraught by the loss of their church and leader, congregants continued, in secret, to honor Vesey’s revolutionary ideals.

Vesey inspired Black activism throughout the nation. To abolitionists, he was a hero and a symbol for freedom. Frederick Douglass was the first to use Vesey’s name as a battle cry. The all-Black infantry in the Civil War would use it again–“Remember Denmark Vesey of Charleston,” they cried as they marched into battle.

The Civil War achieved what Vesey could not: the abolition of slavery. But Blacks would not truly be free until 100 years later.