On Saturday, Jan. 12, the Brooklyn Museum hosted a roundtable discussion about the use, misuse and interpretation of the Black female body in visual culture. The panelists included Deborah Willis, Isolde Brielmaier, Carla Williams and Tisa Bryant. A second discussion followed with author Michaela Angela Davis.

While those discussions allowed the audience of mostly women a safe space in which they could express their feelings, vent their frustrations, challenge their own interpretations and reaffirm and embrace their beauty, the one woman who hit the nail squarely on the head was Brooklyn artist Mickalene Thomas, whose exhibit “Origin of the Universe,” currently on display at the museum, was a reference point for the ensuing discussion.

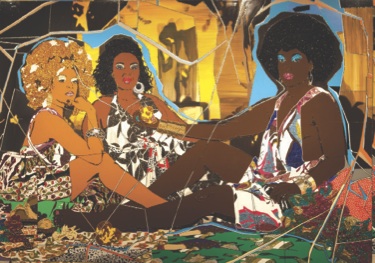

Thomas rocks some major moxie as an extraordinary artist of mixed media, working with paint, collage, photography, interior design and documentary, cutting directly to the chase. The dazzling show hits like a sonic boom, engulfing its audience in the full throttle of Black female beauty, resplendent in all its soulful glory. I say “soulful” because that’s the first thing that came to my mind as I stepped into the exhibition space. I was immediately transported back to the 1970s and the era of Black Power and Soul Train chic.

It started with the title piece, “Origin of the Universe,” a glorious multilayered collage of Black female genitalia, complete with rhinestones that accented just the right places–arresting and breathtaking in its absolute beauty and detail. From there, it was one unabashedly splendid Black woman after another: the three girlfriends, the get-down girl, the lady with the veil who still gets her groove on. We all know at least one of them.

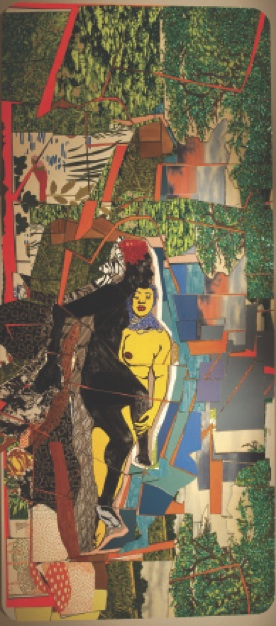

Thomas takes the female form as depicted by European artists–Gustave Courbet’s “Two Friends,” Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” and Auguste Renoir’s “Odalisque,” among others–then infiltrates and reimagines those works, rebirthing them as fresh, modern celebrations of Black womanliness. They re-emerge with bold features, bold adornments, fine afros, full breasts and rhinestone lips, eyelids and fingernails, decked out and with attitude to spare. Courbet’s “Two Friends” is reimagined in the exhibit as a collage in “Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires.” The artist’s own alter ego appears in collage as “Qusuquzah, Une Tres Belle Negresse #2” and “Qusuquzah, Une Tres Belle Negresse #3,” her lips, eyes, collarbone and delicate veil all interpreted with rhinestone accents.

Thomas embraces the Black woman right down to the space she inhabits with three rooms, designed and done up as only a Black woman would. I marveled at the familiar details: the stack of 8-track tapes, the heavy glass ashtray with its ever-present butt, the colorful patterned couch throw that magically matches everything in the room, the record player. I’ve seen these rooms and have lived in them.

The most stirring, personal and poignant part of the exhibit is Thomas’ homage to her mother, whom she uses as the subject of a raw and real documentary short. Her mother, a beauty in her prime, wanted to be a model. Thomas makes her one in the film.